Best-selling author Jeff Pearlman talks Bo Jackson as highly anticipated biography hits the shelves

For much of the past 18 years, Jeff Pearlman has been stuck in the past. But for him and the millions of readers who have devoured his New York Times best-selling sports biographies, that’s a very good thing.

Since the release of “The Bad Guys Won,” his rip-roaring, page-turning account of the 1986 world champion New York Mets in 2004, Pearlman has crafted nine other captivating sports books, including “Football for a Buck,” about the original USFL, “Sweetness,” writing beautifully and dramatically about the late, great Walter Payton, and “Gunslinger,” chronicling the unlikely rise of a gutsy Mississippi quarterback known as Brett Favre.

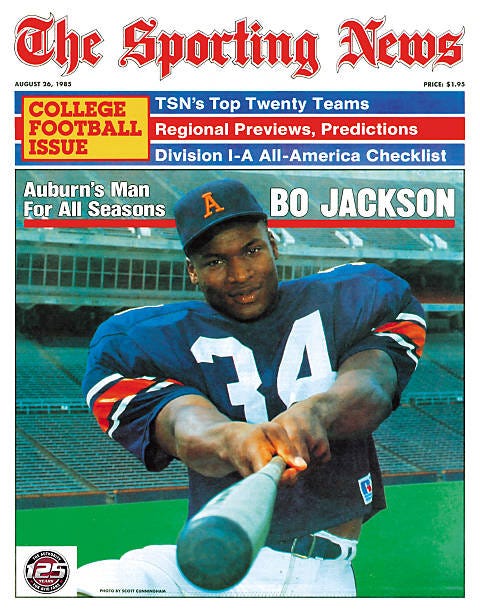

Pearlman, a former Sports Illustrated, Newsday and ESPN writer, is back offering sports fans another in-depth look at one of the most awe-inspiring and mysterious athletes of the last 35 years: Bo Jackson.

“The Last Folk Hero - The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson,” hits bookshelves on Oct. 25. Before hopping on a flight, Pearlman graciously took time out of his busy schedule for a phone interview with NFL Rewind. The prolific author and host of the “Two Writers Slinging Yang” podcast, discussed several topics including why he chose Bo as his latest project, some of his subject’s amazing feats on the gridiron and baseball diamond, and whether or not Bo is the biggest “what if” in sports history.

NFL Rewind: Your book, “The Last Folk Hero - The Life and Myth of Bo Jackson,” comes out on Tuesday. How are you feeling? Stressed? Excited? Giddy?

Pearlman: Definitely not giddy. Stressed and excited. It’s kind of like running a Substack in a way. You really want it to do well. You hope people will see the work you put in, and at the same time a lot of it’s out of your control. Does it get a buzz? Does the topic interest people? Is it the right time? It’s coming out during the World Series and it’s coming out in the heat of the mid-terms… there are just a lot of variables. You never really know. One thing I’ve learned — and this is book No. 10 — you can do as much as possible; you can bust your ass promoting the thing, but at the end of the day, a lot of it is luck.

NR: I know from listening to your podcast you choose subjects for your books very carefully. You’re devoting at least two years of your life to this, so why Bo?

Pearlman: I’m very, very nostalgic. Like very, very nostalgic. Probably unhealthily nostalgic. I sort of envy people who just never look back, they just look ahead. I wish I could do that. I try. It’s hard. But with sports and books that’s OK. I grew up loving Bo Jackson. I had posters on my wall in high school, college. I was very intrigued by him. Blown away by his exploits. And then he got hurt and just kind of vanished. It’s not that often when Superman comes along, and he’s as close to the human embodiment as you can get in sports and then his kryptonite is a freak tackle in a playoff game in 1991. Then he kind of vanishes. Plays a few more years and just vanishes.

I found it really intriguing. The idea of this guy who came along before the internet, who’s supposedly did all these things, these tall tales. Did they really happen? I thought he was a really interesting subject.

NR: I was a kid in the late ‘80s and was really getting into sports. I remember that “Bo Knows” campaign because it was everywhere, right?

Pearlman: Oh, it was huge. And it’s actually a cool story in the book, which I didn’t know. The one ad in particular, where it has like Michael Jordan, John McEnroe and Wayne Gretzky, all those athletes and ends with “Bo, you don’t know Diddley” with Bo Diddley saying that. That premiered during the 1989 All-Star Game. It was a big, big, big investment for Nike. Tony LaRussa had him leadoff in the ‘89 All-Star Game and he leads off with a home run. All the Nike executives know the “Bo Knows” ad is coming out shortly and they’re watching the game at Mickey Mantle’s restaurant in Manhattan, and they all just go CRAZY when he hits that home run. He winds up winning the MVP of that game and it’s just the serendipity of running that ad that day, that game, that moment. … Ronald Reagan and Vin Scully calling the home run. Perfect, clear sky. Beautiful day. Packed stadium in Anaheim. It was just the perfect, perfect moment for “Bo Knows” to really go to another level.

NR: He has this tremendous two-sport run for a few years and one nasty hip injury in a playoff game against the Bengals changes everything. Is he the greatest “what could have been” in sports?

Pearlman: I think he has to be. I really do. There have been a ton of athletes who’ve come along through the years. Some prospect who gets hurt early on… Len Bias is certainly one, a huge what if. They come along every now and then. But Bo was so unworldly gifted that it wasn’t just another running back. Say Trevor Lawrence got hurt tomorrow and could never throw another pass. People would be like, “Oh, that’s really a shame, he could have been something,” but nobody would be like, “Ah, he could have been the greatest quarterback of all-time.” There’s this idea that Bo Jackson could have been Mike Trout or he could have been Eric Dickerson. Maybe, but we’ll never know and that’s sort of the intrigue of it all, we’ll actually never know.

NR: I know you pour a ton of work into your book projects. How challenging was working on Bo compared to your nine other books?

Pearlman: Every book has its challenges, but this was the first book I had to write during a global pandemic. I couldn’t travel very much. I wound up going to Auburn and I went to Bessemer where he’s from. I was able to go to the main branch of the Birmingham Public Library, which was really great. But I would have liked to travel a lot more, see different places. Maybe spend more time at Auburn, more time in his hometown. Also, he’s guarded as guarded can be. I spoke to him early on. He’s very nice, but he’s like, “Yeah, people approach me all the time. I’m not going to help you. It’s fine if you do it, but I’m not going to help you.” That happens a lot when you write biographies of living people. But I interviewed more than 700 people, I dove hard in. It’s always a challenge when a guy doesn’t talk. Never makes it easier. Some people are like, “Oh, is that good that he didn’t talk?” How would that make it good? How is that a benefit? But it does make you work harder.

NR: Like Favre, he didn’t talk to you for “Gunslinger.”

Pearlman: Yeah, but his whole family did, so that worked out.

NR: In reporting, I always feel like there are workarounds. Sure, it’s frustrating when a source doesn’t get back to you, but you resort to plan B, C, D. …

Pearlman: Well, I got really lucky here because someone told me early on in my research that Bo had an autobiography come out back in 1990 called “Bo Knows Bo.” The late Dick Schapp wrote it. Schapp donated all of his transcripts, notes, audio to the Auburn University Library and I paid the library just to send me copies, so I had hundreds of pages of transcripts from 28-year-old Bo, probably the vast majority of that was never used in the book. That was an absolute goldmine.

NR: What was the most fun part about working on Bo?

Pearlman: I guess in a way it was like taking these mythological stories and breaking them down piece by piece. Even the moments. Bo climbing the wall in Baltimore. Finding all the people involved, finding the story behind it. Someone told me that when Bo was in high school, he hit a ball in a game and it went so high and he was so fast that by the time it came down he was rounding third base. I thought, “That doesn’t really sound plausible,” but I kept hearing people tell me “No, I was there when it happened.” Finally, I found Eddie Scott. He played for Fairfield High School. He was the leftfielder in that game. He’s like, “It’s 100 percent true. I was playing in the outfield, he hit this ball, it was ridiculously high, I couldn’t even find it. It finally came down, hits the grass, I look up and Bo is rounding third and heading for home.” I really enjoyed taking these stories and trying to break down what’s real, what’s not real. How did it really happen and how great of an athlete was this guy?

NR: A lot of people don’t recall that he wasn’t originally drafted by the Raiders, right?

Pearlman: No, he was drafted by the Buccaneers. He was the first pick in the ‘86 draft. When he was a senior at Auburn, midway through the baseball season, the Buccaneers had the first pick and the owner sent the team plane to Auburn to pick Bo up on a free day, fly him to Tampa, get him a physical and fly him back. Obviously, Bo didn’t know (at the time), but that flight cost him his eligibility for baseball. He was not allowed to play anymore baseball for Auburn. He was livid. He blamed the Buccaneers, blamed the guy who was representing him and pretty much swore he would never play for the Buccaneers. They ignored his warning and still drafted him No. 1 and he never signed. Went on to sign with the Kansas City Royals. When the draft was held again in ‘87, the Raiders, who were tipped off that Bo wanted to play for them, used a late pick to draft him. They gave him all the options in the world: play baseball, take a week off, two weeks off, whatever you want. … They paid him a lot of money to be a part-time player.

NR: I know you don’t want to give too much away; you want people to read the book, but what was your biggest surprise from your research into Bo?

Pearlman: Hmmm, good question. He was this phenomenon and he suffered. Everything came easily to him athletically. Always. Since he was a kid. I hate being lazy and saying, “Oh, Bo was a natural athlete,” but he really was a naturally gifted athlete. And then he gets hurt with the hip injury and he became a workhorse. It’s almost like when he got hurt and he no longer had the natural gift of speed and automatically generated power from his hips, he didn’t have it anymore, all of a sudden, he became this guy you had to root for. It’s like he went from being “Everybody’s All-American” to being “Rudy” in a very short period of time. All of a sudden, he knew what it was like to be a fifth outfielder fighting for a spot. He knew what it was like being an undersized middle infielder. He had a malfunctioning hip; he had no lateral movement whatsoever and he became really embraceable and really human. One of the most amazing accomplishments nobody talks about is that this guy played two full major league seasons on a shitty artificial hip. Not like an artificial hip you’d get today. Andy Murray in tennis came back with an artificial hip. If Bo Jackson had that artificial hip in 1991, he would have made almost a full comeback. But he was playing on an artificial hip your grandma would have. It was made of plastic. It had metal bolts. When you moved the hip, the metal would rub against the plastic and little shards of plastic would go off into your body. It was a piece of crap and for him to come back and produce at a Major League level, not a superstar, but a legit DH, it’s one of the great accomplishments I’ve ever written about or recorded.

NR: This is kind of a loaded question, but here goes. Assuming he doesn’t suffer the hip injury in ‘91, in your opinion, does he make the Pro Football Hall of Fame, the Baseball Hall of Fame or both? Or neither?

Pearlman: It kind of depends on what you believe. There’s a caveat to this. He said he was going to play one more NFL season and then stop. So, if that had been the case, he wouldn’t have made the Pro Football Hall of Fame. I don’t think he was quite a baseball hall-of-famer. He had all the talent. I mean he really had Mike Trout talent, but he really didn’t dedicate himself to the craft. I mean he was playing football; he wasn’t putting in the offseason work. He wasn’t going to Arizona Fall League, wasn’t doing Instructional League. There were a lot of holes in his game, but he was so athletic he made it look easier than it was. Now, if you forget all that and he went on to play 10 years in the NFL, I think he’s arguably the greatest running back who ever lived. I truly do. Coming out of Auburn, if he decided to just play baseball for the next 15 years, I think he’s Mike Trout. He takes it seriously, he’s Mike Trout. He’s that kind of player. He just needed a lot of work and a lot of discipline in his game.

NR: Next up, from listening to your podcast, it sounds like you’re working on a multi-book memoir about your early journalism days at the Nashville Tennessean?

Pearlman: Well, one of the books is a memoir, so that will be weird. I don’t know if five people will care but it’s a book I’ve always wanted to write.

NR: I think it’s a great idea. I actually started writing one a few years ago about my early days in journalism. I got fired twice, all within less than a year! But then I got preoccupied with other things and kind of forgot about it.

Pearlman: I don’t know. It’s just something I’ve wanted to do. There’s no reason to think it’ll be a huge seller but sometimes you can write something on a passion and I had the worst two-and-a-half-year career ever for any journalist in Nashville. I mean it was great for all the learning experiences, but I was a total fuck up that nobody would ever want to encounter in their life, so hopefully I’ve learned from it.

NR: Ha, I think so. Well, thanks so much for joining me today, Jeff.

Pearlman: Thanks for having me. I appreciate it, man. Good luck on the Substack.

Editor’s note: You can buy Jeff’s book pretty much wherever books are sold, including here.